If you’re about to have your first video capsule endoscopy (VCE) or simply wondering what the experience is like then read on. I underwent my third procedure in September 2023, each one has been slightly different.

Fantastic Voyage – revisited

In November 2018 I had my first VCE and afterwards published a blog post “Fantastic Voyage” as it reminded me of that sci-fi film about a submarine crew who are shrunk to microscopic size and venture into a body to repair a damaged organ. What follows updates that post and then goes on to describe the two further procedures.

Why did I need a VCE in the first place?

I was feeling fit, well and with a good QOL. Colonoscopies, endoscopies & biopsies were all clear but… test results were suggesting the opposite – calprotectin approaching 2000 (normal range 50 to 100); Hb hovering around 110 (not particularly low but on the way down); and I was losing weight (down by 15kg). The only part of my digestive tract that hadn’t been seen through a lens was the small bowel between duodenum and my anastomosis, where my large and small intestines had been rejoined after an ileostomy in 2010.

With a capsule there is always a risk of it becoming stuck so as a precaution a radiologist was asked to review my last MRI scan for strictures before the VCE was ordered. The alternative is to swallow a patency capsule which is a dissolvable pill that surrounds a small radio frequency identification (RFID) tag that can be identified by an X-ray or CT scan. If the pill become lodged in the gut it simply dissolves. The latest cost (2025) that I could find for an NHS capsule endoscopy procedure is £747.

The pre-procedure instructions were similar to having a colonoscopy but with none of the dreaded prep solution. The leaflet listed the medications that would have to be put on hold. These included iron tablets and loperamide 7 days out. Iron tablets – no problem, but loperamide – that was one instruction I didn’t follow. The thought of taking a trip to London without having taken it for 7 days was not even worth considering.

On arrival at the GSTT Endoscopy Department a specialist nurse outlined the procedure and ran through the risks. In the worst case scenario the capsule could become stuck and need surgery to recover it!

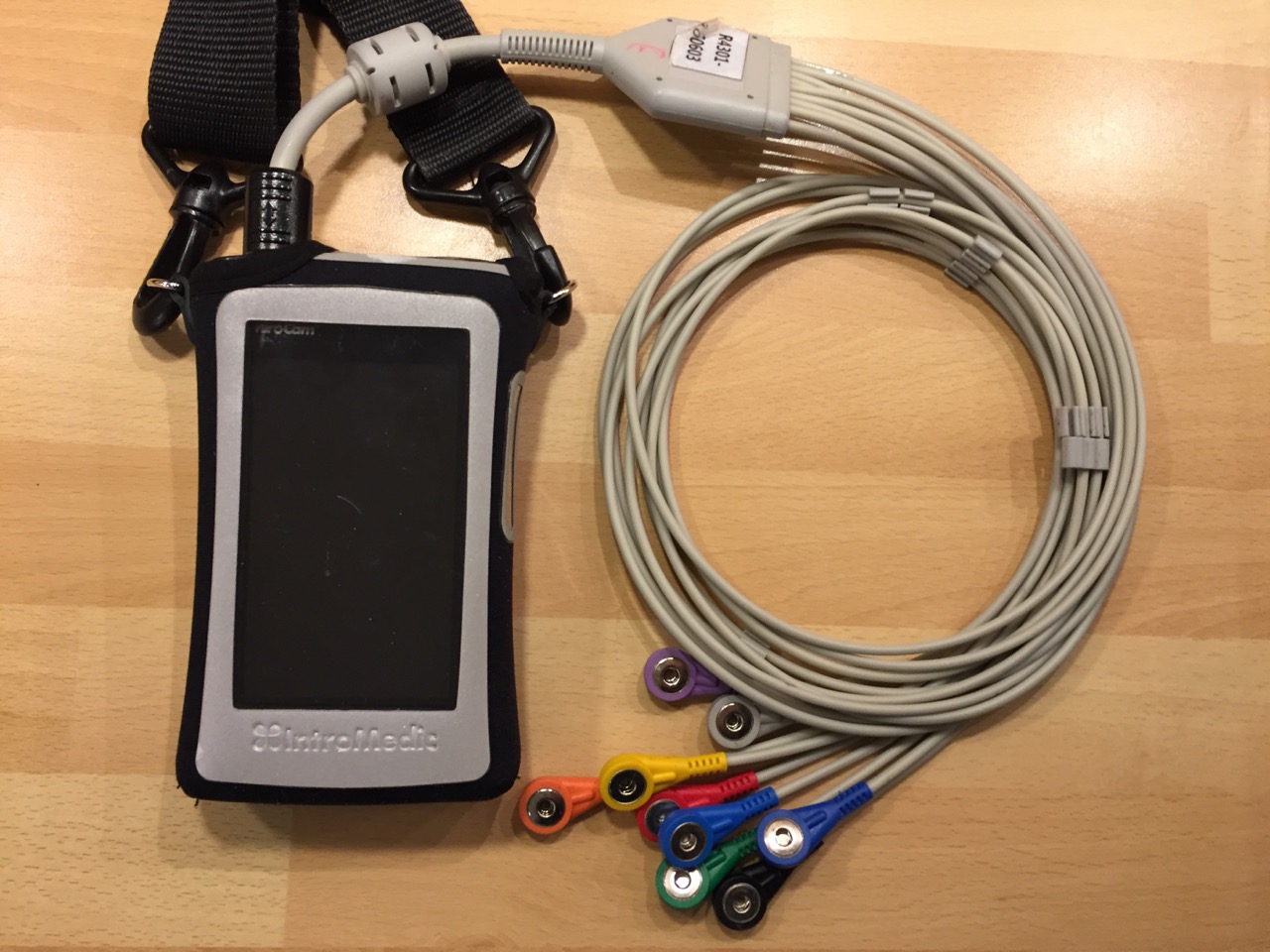

Several different camera systems are on the market, all working on similar principles. There are also different types of capsule for specific tasks. The more advanced ones have higher resolutions & frame rates and some communicate with the recorder unit wirelessly, without the need for sensors. In this instance the MiroCam system was being used with its array of sensors picking up the capsule signal and sending it to the recorder.

The first task was to attach the numbered sensors in the correct positions around the abdomen and connect them to the wiring harness, very similar to an ECG. The harness itself was quite bulky. The nurse then produced the capsule, asked me to hold it between my fingers then pass it in front of the recorder unit. A bleep showed that they had paired. My information had already been entered into the recorder unit with the display showing name, hospital number etc.

How easy was it swallowing the capsule?

The answer, for me, was very easy. One gulp of water and it was on its way. The nurse switched on the live monitoring function and we watched it enter my stomach. To save battery power she then switched it off and I didn’t have the courage to try switching it on again in case I ruined the whole procedure (…and what if I had seen something that, to my eyes, looked wrong? A surefire way of inducing hypochondria).

The unit had a 12 hour battery life and switched itself off automatically after that time had elapsed. I could then remove the sensors and return the recorder unit. The results were due in two weeks time.

When would I be able to eat and drink again? Coffee two hours after swallowing the camera, a light meal after another two hours and then resume normal eating after six hours. You’ll be pleased to know that the camera is not retrieved after the procedure (although there are some types that do rely on the patient “collecting” it and returning it to the hospital for analysis!).

Wearing the receiver unit took me back to having a stoma as it was hanging in the same position as the bag and the adhesive on the sensors gave a similar sensation to that of a stoma backplate.

When the report was available it showed that Crohn’s had re-surfaced in my small bowel in the form of mild to moderate inflammation. This was a disappointment as I had been in drug free remission since 2011. A printed copy of the endoscopy report, in glorious living colour, arrived in the post. I was intrigued by the transit times : 15 minutes to make it through the stomach; 2 hours 52 minutes travelling through the small bowel; and 8 hours 51 minutes in the colon. These were classed as being “within average range”.

Luckily there was a summary report; unluckily there it was in black and white “…with a background of Crohn’s these are in keeping with mild to moderate active disease”. As a result I was started on Vedolizumab.

Video Capsule No.2

In August 2020 I received a call from Endoscopy appointments to arrange for a follow-up VCE to see if the inflammation in my small intestine was still there. I would need the obligatory small bowel MRI first to ensure there were no strictures that could trap the capsule on its journey.

We were in the depth of COVID restrictions and the procedure was considered to be an AGP (Aerosol Generating Procedure) and as a consequence I needed to have a negative COVID result 3 days prior to the hospital visit. It was arranged for a courier to deliver a test kit, wait for me to carry out the test and then return it to GSTT for analysis. It turned out negative.

The endoscopist had been working at GSTT for 15 years but, surprisingly, our paths had never crossed. He explained that the hospital had access to 7 different camera systems and that their prominence as a leading teaching hospital meant that manufacturers were keen to make their systems available. The one they would be using that day was made in Wuhan (yes, THAT Wuhan) and was the first one to include a type of AI which highlighted frames needing particular attention when reviewing. Two representatives from the manufacturer sat in on the procedure to observe it being carried out.

Unlike my previous VCE this capsule transmitted directly to a receiver worn on a belt without the need for sensors. It was a lot more convenient. The output from the camera was displayed on the receiver and also on a laptop.

I asked if it would be possible to examine my oesophageal varices to see if they needed banding. I was hoping to avoid a conventional endoscopy later in the year. Yes, it would be possible by adopting an “oesophageal protocol”, a fancy way of saying you lie down as the camera is swallowed so that the passage through to the stomach is slowed down. Swallowing it whilst lying down was not as difficult as it sounded but even so it only took a few seconds before it entered my stomach.

I lay on a pivoted bed. It was tilted head first, feet first, then left and right so the camera could video all around the walls of my stomach. A patch of inflammation appeared. It would be discussed at the next MDM on Friday. Eventually the camera was allowed to pass into the duodenum and it was time to get back on my feet.

I returned to St.Thomas’ the following day to drop the recorder belt back. Eventually the follow-up letter arrived from the VCE Virtual Clinic. It was good news, very good news. The vedolizumab was doing its job.

Video Capsule No.3

The same again but different : In March 2023 I ended up in our local A&E with internal bleeding. An upper GI endoscopy showed oesophageal varices had regrown despite being OK when checked a few weeks previously. What had caused them to reappear?

A small bowel MRI scan picked up a new clot in my superior mesenteric vein and I went to see a thrombosis consultant. Our discussion boiled down to should I start on blood thinners, something I had declined in the past. Before making the decision he wanted to make sure that I was not bleeding in locations other than my oesophagus hence requesting a VCE.

When the nurse rang to arrange the date for the procedure she said that she would be including sachets of MoviPrep. I remarked that a) I hadn’t had to take prep on the previous occasions and b) if I had to then I would prefer Citrafleet. The instructions arrived together with the Citrafleet.

The preparation was now virtually the same as having a conventional colonoscopy with the same restrictions on the type of medications and the timing of meals during the countdown to procedure day.

(Having had the conversation about not having prep I recalled that when I had been through our medicine cupboard I had found a sachet of MoviPrep and assumed it had been sent for some colonoscopy in the dim and distant past. Maybe I hadn’t used it prior to a previous VCE.)

This time the capsule was the two lens version which results in it being larger than the previous ones I had swallowed. That didn’t present a problem but then I have become used to swallowing pills and capsules. Out of curiosity I asked the nurse how they would administer it if someone couldn’t swallow and she replied that it is possible to introduce the capsule with an endoscope!

The set-up was slightly different from before. There was a disposable belt with built-in sensors, fastened with velcro around the waist. A cable connected it to the recorder unit hung over one shoulder. Apart from that the operation was as previously described and at exactly 12 hours from the start the receiver bleeped and switched itself off. I returned the recorder to GSTT the following day.

I mentioned to the nurse that I had a follow-up appointment with the thrombosis consultant in two weeks time. She said that it should be possible to have, at least, a preliminary run through by then but you have to remember there are nearly 100,000 frames produced.

…and then I had a short wait until talking to the thrombosis consultant and deciding if I should start taking blood thinners. By the time of the tele appointment with him the VCE report was available. We covered a lot ground, probably too much to take in to be honest. My case had been discussed at the Thrombosis Radiology MDM and the decision was to not start anti-coagulation. I was quite happy not to be taking even more medication!