A New One On Me

Over the years I have undergone many different tests but the one that had eluded me to date was the Video Capsule Endoscopy (VCE). Maybe that’s the wrong to put it. Might be better to say that “so far I hadn’t needed one”.

So what changed? The last time I saw my gastro we discussed the apparent conflict between my feeling fit and well (good QOL), clear colonoscopies & biopsies but test results suggesting the opposite – calprotectin = 1300 ; Hb = 11.0 ; gradual weightloss >15kg. We had discussed this before. He had even asked a colleague to carry out a second colonoscopy in case he had missed something. Both of them were stumped so we agreed to park it. I thought now was the time to ask for it to be investigated further. The only part of my digestive tract that hadn’t been seen through a lens was the small bowel between duodenum and the point where my large and small intestines had been rejoined. He agreed.

We had previously discussed using a self-propelling endoscope but a “pill cam” sounded a less daunting solution. The concern about using a capsule was the risk of it becoming stuck at a narrowing. A radiologist would be asked to review my last MRI scan for strictures before the endoscopy was ordered. The cost of the capsule endoscopy procedure to the NHS is approx. £500.

All must have been well as I got a call from Endoscopy Appointments to agree a suitable date for the procedure. A couple of days later the instructions arrived in the post. Very similar to having a colonoscopy but with none of the dreaded prep solution needed. The leaflet also listed the medications that would have to be put on hold. These included stopping iron tablets and Loperamide 7 days out. Iron tablets – no problem, but Loperamide – that would be the one instruction I wouldn’t be following. The thought of taking a trip to London having not taken Loperamide for 7 days was not even worth considering and would have put in jeopardy attending the Big Bowel Event at the Barbican on 16th November.

Monday 19th November 2018 – GSTT Endoscopy Department

After the glorious weather over the weekend it was a disappointment to arrive in London on a dull, rainy day. The walk to the hospital took me past a number of foodstalls that simply reminded me that I hadn’t eaten since 8:30 the previous morning or drunk anything since 22:00.

I arrived at St.Thomas’ Hospital and, after a few minutes’ wait, was collected by the specialist nurse. She asked the usual questions :

“When did you last eat?” “8:30 yesterday”

“When did you stop taking iron tablets?” “7 days ago. Why is it so far in advance?” “They blacken the walls of the intestine and can give patients constipation”

I explained that I hadn’t stopped taking Loperamide as, for someone who relies on it every day, any thought of stopping for 7 days was a definite non-starter.

“What other medications are you on” I went through the list

She outlined the procedure and I was able to ask the questions. The main one was “can the capsule be used to judge the condition of esophageal varices? If it can then should I cancel my conventional Upper GI endoscopy booked for the week before Christmas?”. She explained that a capsule can be used to look at varices but it would need to be a different type from the one I would be swallowing today.

She then ran through the risks of the procedure. The main one being the capsule becoming stuck and the possible means required to extract it, the worst scenario being surgery. I signed the consent form.

There are several different makes of capsule system available which all work on similar principles. There are also different types of capsule for specific tasks. There is even one with a camera at both ends.

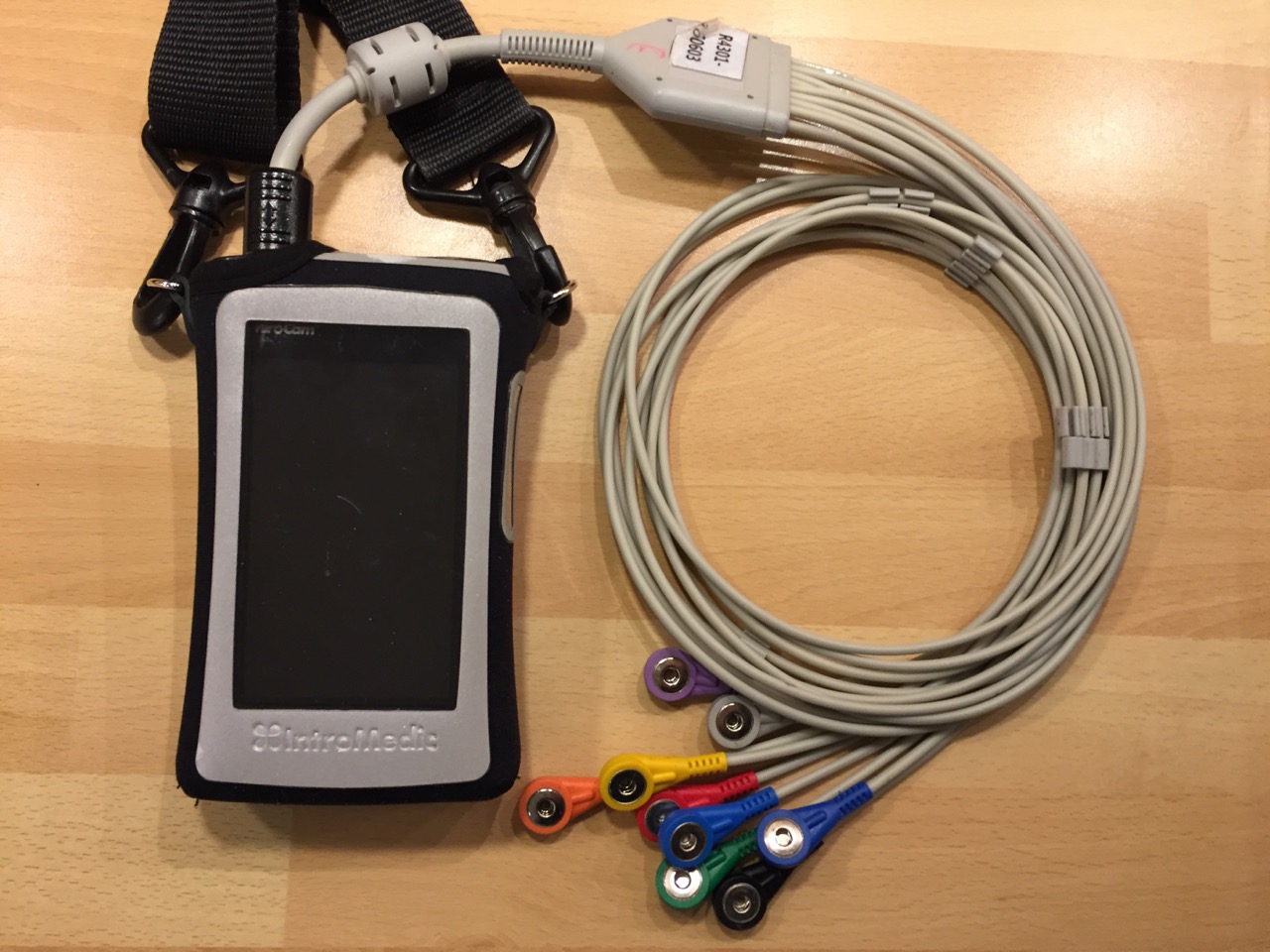

The more advanced ones have higher resolutions & frame rates and some communicate with the recorder unit wirelessly, without the need for sensors. St.Thomas’ employ the MiroCam system which uses an array of sensors to pick up the signal from the capsule and send it to the recorder. (It’s the same unit that the BBC used for the live endoscopy that they broadcast as part of their “Guts: The Strange and Mysterious World of the Human Stomach” in 2012.)

The first task was to attach the numbered sensors in the correct positions around the abdomen. I can see why wireless communication is the future. (I wouldn’t normally post a selfie of my abdomen, in the interests of good taste, but to illustrate…..)

Once they were in position the nurse produced the capsule and asked me to hold it between my fingers then pass it in front of the recorder unit. A bleep showed that they were now paired. As she had already input my information into the unit the display showed my name, hospital number etc.

It was time to see how easy swallowing a capsule would be. The answer – very easy. At 11:40 I took one gulp of water and it was on its way. The nurse switched on the live monitoring function and we watched it enter my stomach. To save battery power she then switched it off and I didn’t have the courage to try it myself in case I ruined the whole procedure. (…and what if I had seen something that, to my eyes, looked wrong? A surefire way of inducing stress)

As the unit has a 12 hour battery life she said the unit would switch off at 23:40 and I could then remove the sensors. The recorder unit would then need to be returned to St.Thomas’. I explained I was not available the following day so we agreed that I would take it back on Wednesday. Two weeks later the results should be available. When would I be able to eat and drink again? Coffee two hours after swallowing the camera and then a light meal after another two hours.

If it had been decent weather I would have set off on a long walk around London, as light exercise helps the transit of the capsule, but I decided I would rather get home in the warm. I took a short walk to College Green (the area outside the front of the Houses of Parliament) to see if there was a media scrum due to some new development with Brexit but there wasn’t so jumped on the Tube to Blackfriars and took the train home.

True to the nurse’s word the unit switched itself off at precisely 12 hours from the start of the procedure and I was able to peel off the sensors with remarkably little pain. The camera is not retrieved after the procedure (although there are some types that do rely on the patient “collecting” it and returning it to the hospital for analysis).

Wearing the receiver unit took me back to having a stoma as it was hanging in the same position as the bag and the adhesive on the sensors gave a similar sensation to that of the stoma backplate.

Partial Update

The analysis of the video was due to take 2 weeks from handing the recorder unit back but nothing was forthcoming. I contacted my gastro consultant who said he would chase it up but after 4 weeks still nothing. I knew I would be visiting the Endoscopy Dept. again on 18th December, for my annual Upper GI scope (looking for esophageal varices related to portal vein thrombosis) so I would ask then.

The endoscopy was being carried out by the head of the Gastro Dept. so I asked him whether he could find my video results on the system. He went off to check the status. By the time he returned I had been prepared for the scope – xylocaine spray (burnt bananas) to back of throat; mouthguard in position; Fentanyl injected. I was unable to speak. Luckily they had held off with the Midazolam so I was, at least, still conscious!

He told me that the video was being checked now but he had seen the first half of it and appeared to show Crohn’s in my small intestine. A nice Christmas present! I would have to await the full analysis before discussing the way forward. I emailed my gastro consultant to tell him the news. He replied that he would keep an eye out for the report.

…and with that the Midazolam was injected….zzzzz

When Will It Be Resolved?

The report took a long time to finally emerge and in another email my gastro said that it did indeed show that Crohn’s had re-surfaced in my small bowel in the form of mild to moderate inflammation. This was a disappointment as I had been in remission since 2011. An appointment has been arranged for 15th April to discuss the treatment options. If feasible I would favour the “do nothing” option. My thoughts on the end of remission and the questions I have for my gastro are in a separate post (opens in a new window) – https://www.wrestlingtheoctopus.com/call-my-bluff/

The Report Finally Arrives

In mid-March a printed copy of the endoscopy report, in glorious living colour, arrived in the post. Whilst I found it fascinating I struggled to understand exactly what the images were showing.

I was intrigued by the transit times : 15 minutes to make it through the stomach; 2 hours 52 minutes travelling through the small bowel; and 8 hours 51 minutes in the colon. These were classed as being “within average range”.

Luckily there was a summary report; unluckily there it was in black and white “…with a background of Crohn’s these are in keeping with mild to moderate active disease“.